The UK’s proactive stance on blue hydrogen could give a leg up to its embattled refining industry, according to Essar Energy Transition (EET) Fuels, as it readies for a low-carbon future at its 200,000 b/d Stanlow refinery.

EET, a subsidiary of Indian multinational Essar, has been one of the few prepared to take big bets on the UK’s downstream sector as other large players have withdrawn. Spooked by the threat of declining fossil fuel demand, rising carbon taxes and large, low-cost foreign competitors, Shell, BP and TotalEnergies have all shed UK refining assets since the turn of the century, while Petroineos recently confirmed it will close its 100-year old Grangemouth refinery in Scotland early next year.

In contrast, EET has banked on demand for premium, low-carbon fuels at Stanlow, footing a $1.2 billion bill to decarbonize the site over the next five years.

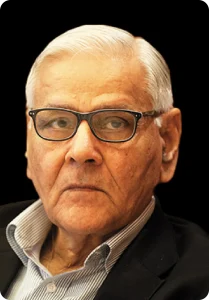

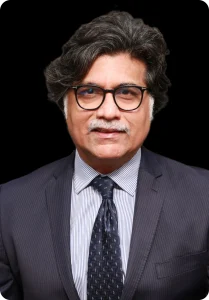

“We have taken the conscious decision just to do stuff,” Viral Gathani, the company’s Senior Managing Director – Strategy, M&A and Finance, told S&P Global Commodity Insights in an interview in October. “Initially it’s costly. Even despite all the government support it’s a big call.”

Decarbonization investments in the refinery should cut emissions by 95% by 2030, according to EET estimates, with new hydrogen capacity set to replace natural gas used in the refinery process and, from 2027, feed a custom-built power station for the site.

EET Hydrogen, a partner company, plans to begin construction on its 350-MW HPP1 blue hydrogen plant in 2025, promising to cut natural gas demand at Stanlow by around two-thirds, Gathani said. An additional 1 GW is planned to later come online via a second plant, HPP2, while industrial carbon capture is planned for 2028.

The ambitious plans limit exposure to UK carbon prices under the UK emissions trading scheme (ETS) as industrial sites are obliged to pay for growing proportions of their emissions. Platts last assessed the UK Allowance nearest December contract at GBP37.90/mtCO2e Nov. 1, well below record levels of close to GBP100/mt, though analysts project prices to rise again as demand is forced higher.

The revamped refinery will also offer consumers fuel with a 6%-7% lower lifecycle carbon footprint, Gathani said, potentially offering Stanlow a competitive advantage in the future if transport fuels are included in the scope of an expanded ETS.

Blue hydrogen support

A key beneficiary of early government support for decarbonizing the UK’s industrial clusters, EET’s HPP1 plant was among the first three emitter projects to get the green light under a Track 1 GBP21.7 billion ($28.5 billion) funding plan.

EET Hydrogen has pushed back a final investment decision on HPP1 to 2025, following delays to government funding allocations to associated CO2 transport and storage infrastructure.

The government is yet to announce how subsidies will be allotted between projects approved at the start of October, but Gathani said that the bulk of the funding would likely be directed to capital-intensive CO2 transport and storage infrastructure, rather than emitters in the East Coast cluster and HyNet, where Stanlow is located.

Nonetheless, Gathani said that government subsidies expected to secure blue hydrogen for offtakers at the price of natural gas provide a strong stimulus for emitters to invest in the switch early.

“There’s no excuse for not taking hydrogen if you’re an industrial company, because it’s the price of gas, and they’re giving grants for companies to put in the equipment,” he said.

A proactive approach to blue hydrogen could give the UK a head-start on other European governments that had until recently prioritized green, renewables-based supply, Gathani said, calling stance a pragmatic approach to leverage existing infrastructure.

ExxonMobil recently criticized a lack of policy certainty in the UK for its decision to abandon carbon capture and storage plans at its Fawley refinery near Southampton, though Gathani said that good opportunities remain for other UK refiners. Unlike Southampton, which lacks an existing storage basin to sequester carbon, rivals such as Phillips 66’s Humber refinery could be well-placed to repurpose old gas fields for carbon capture, Gathani said.

CBAM necessity

Bold steps in the UK refining space demand confidence that the government will prevent the industry from failing as it faces a broader threat of deindustrialization, lobbyists have said.

In other high-emission industries, such as aluminum and cement, the government has taken measures to protect producers from high-emitting competitors, though refined products are yet to fall within the scope of a carbon border adjustment mechanism planned for 2027.

Practical difficulties applying the measures to refined products, rather than lack of political appetite, have triggered the delay, Gathani said, remaining confident that allowing Europe’s refineries to shutter would be politically untenable.

“You can’t ask the industry to pay carbon tax as a whole and not give them any mitigation to level the playing field relative to producers in regions without carbon tax regimes,” he said, adding that energy insecurity after the Russia-Ukraine war has added pressure to keep domestic fuel businesses afloat.

Biofuel offshoring

For the growing biofuels market, the case for European production is less clear, Gathani said. Despite Europe’s position as one of the world’s fastest-growing biofuel demand hubs, its refineries lack access to sufficient waste-based feedstocks, while scalable green hydrogen investments could be more economic elsewhere.

Essar had previously announced plans to develop a waste-to-fuel sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) plant at Stanlow with Fulcrum bioenergy, but the project was abandoned as the US company fell into financial difficulty this year.

Meanwhile, concerns over high costs, water use and limits to scalability remain key challenges for municipal waste-based biofuel projects, Gathani said.

SAF production could be one use case for a 40-MW green hydrogen facility planned by EET and SEE for 2028 in northwest England, he said, though high costs remain a barrier. Meanwhile the UK is yet to develop fuel standards for SAF produced from blue hydrogen.

For now, the company has eyed new import routes to the UK from Essar’s Salaya facility in Gujarat, India, where it aims to produce 500,000 mt/year SAF by 2027. SAF at the site will be made with used cooking oil and animal fats, but the group plans to leverage cheap renewable hydrogen costs in India to support future production as it scales.

“It doesn’t deal with your fuel security problem because you still have to get it to the U.K., but it is a significant source of SAF at very competitive pricing,” said Gathani, who said EET is still mulling future production options in the UK.